The antidote to isolation is representation: When we are among people whose lives mirror our own, we feel less alone. To be queer in a world that hunts queerness, to be sober in a society that glorifies drinking, is to challenge “normative” impositions.Īnyone who defies any “norm” knows isolation and sometimes faces (intense) discrimination. Sobriety and queerness are both lived experiences that challenge dominant structures. Preserving all spaces in which queer people feel at home is essential and includes supporting and continuing to create spaces for queer folks who can’t or don’t want to drink. And this celebration can take many different forms. Knowing that these options exist helps me trust that I belong as I am because, ultimately, Pride is a visible protest that celebrates life as a record-number of bills targeting the LGBTQ community are being discussed in state legislatures across the country. New York City had an alcohol-free cruise. This year, the Twin Cities hosted their third annual Sober Pride. Pride also offers options for those of us in recovery. In Asheville, you can visit Firestorm, a collectively-owned, queer, feminist bookstore and community space that is “welcoming, sober, and anti-oppressive.” Queer and sober spaces certainly exist. In San Francisco, you can drink cappuccinos, eat sandwiches and attend a range of events and 12-step meetings at The Castro Country Club. When I expressed this conflict to my therapist, she read me a quote by writer and journalist Johann Hari: “ The opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety – it’s connection.” Through this framework, I began to understand the importance of finding and building a community that reflects me, in order to recover.

It is like trying to explain the sensation of water to someone who has never gone swimming: You have to feel it to know it. I cannot meaningfully discuss this reality with people who may have never faced rejection based on their intrinsic identity. Part of what fueled my addiction was a deep sense of isolation rooted in an estrangement from my nuclear family – my queerness directly informed this estrangement. As a queer nonbinary person, my lived experience makes me a minority, which means I have fewer opportunities to articulate the nuanced way my queerness and my substance use were interrelated. However, when I am in sober spaces, my queerness often feels invisible because straight people dominate most environments, including these. Engaging in what used to be my favorite experiences – queer nightlife in glittering bars – requires silencing the self that fights to stay sober. I wish I were the kind of person who found it easy to abstain when in the presence of alcohol, but for now, I am not. Participating in some of the vibrant ways my community celebrates itself puts my sobriety at risk. I’m homesick for spaces that aren’t safe for me anymore. Part of me wants to return for old times’ sake, but I also know that being there won’t feel the same – because I’m not the same. My old haunts in San Francisco have reopened and are bursting with Pride parties all month. Liam and I just celebrated our eighth anniversary. Now, at 30, I am two and a half years sober from alcohol and 10 months sober from recreational drugs. With support from Liam and a therapist, I quit.

On the other hand, I couldn’t keep drinking and create a meaningful life. On the one hand, I couldn’t imagine life without intoxication. The lockdown’s solitude stripped my drinking of its social disguise: Without the blue neon lights, the music, the crowd, my habit revealed itself as a condition that was destroying my body, mind and marriage.

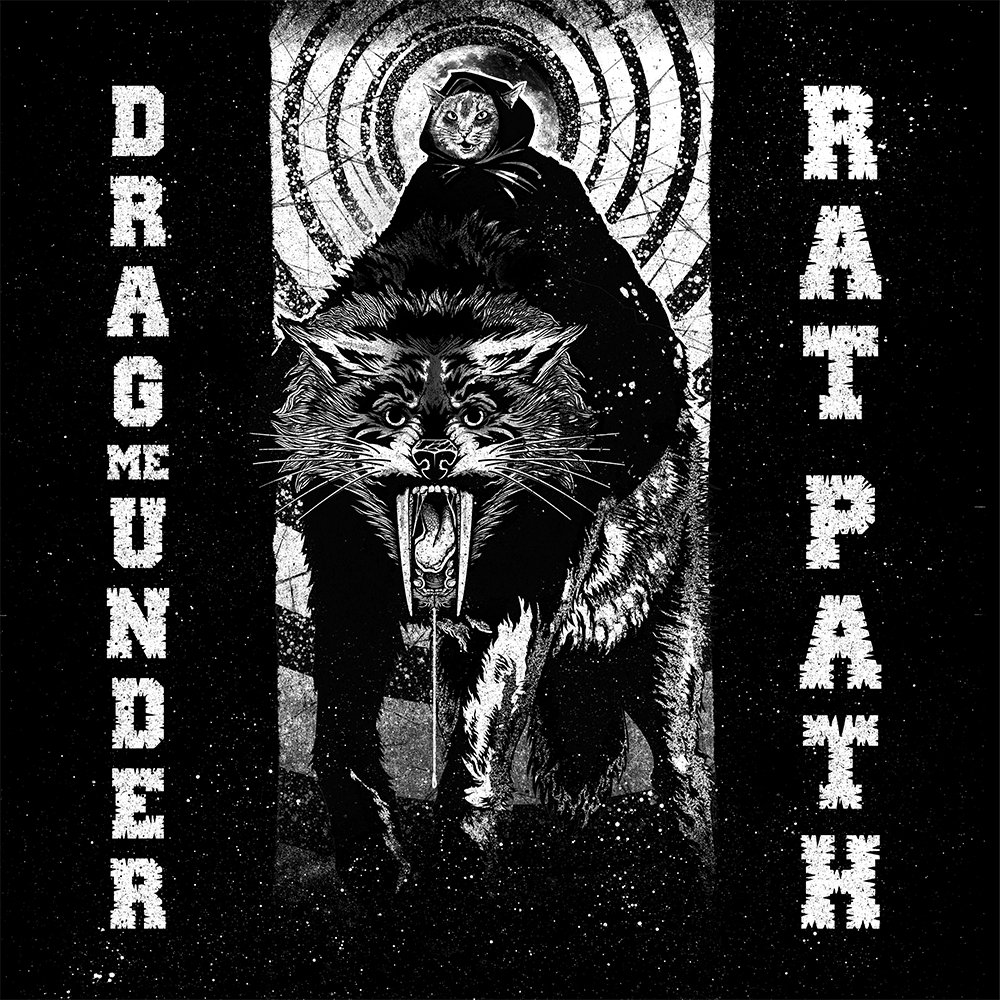

DOWNLOAD DRAG ME DOWN WINDOWS

The bar’s owners hammered wooden boards over its windows and everyone retreated indoors. The pandemic exploded at the height of my addiction. I’d pick fights with Liam and wake up the next morning, clammy and nauseous, trying to recall the wounds I’d inflicted, trying to say I was sorry in a way that sounded different from all the apologies I’d offered before. All the lacerating emotions I drank to avoid – rage, grief, shame, fear – gurgled to the surface. Once the first shot of tequila hit my bloodstream, I became bottomless: Nothing was ever enough. Feeling like I belonged, wholly, was more addictive than the alcohol itself.īut eventually, the fun soured. This glittering bar was the home I’d always wished for. I was in my mid-20s and I thought I was drinking and partying because I was “having fun,” which I was.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)